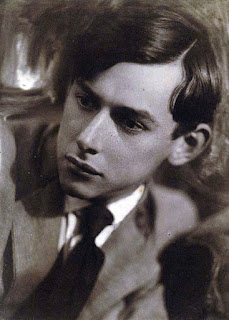

Unattributed illustration from Bonch-Bruyevich’s Lenin and the Children (1975) / Image courtesy of e-Reading

From “Christmas” (1985)

by Timur Kibirov

7

… Yet the Son slept

a sweet sleep, and over His brow

streamed the light from last night’s

8

Star, blending with the radiance

of the scarlet dawn.

Free from anger or sadness,

bubbles formed on

those Lips that yet again would

give the Good News, that would

grimace and spit blood

and praise the merciful Lord…

9

But the news spread, and rumor

filled the world.

At last it reached the Kremlin,

our Russian stronghold.

And the tall blue firs rustled!

The cannon fired for the first time!

A watchman recoiled in terror!

And then from the mausoleum

10

he came. He climbed into the car.

Iron Felix sat beside him.

Behind the wheel was the “Sailor,”*

staring down anyone they passed.

They flew faster than the wind.

They drove up. They knocked.

A smile beamed

from the face of Ilyich.

He had come with New Year’s gifts:

the Peace Decree, saccharin,

a copy of the Great Initiative,

the log he’d hauled at the work party,

11

first-rate provisions, and a bouquet

of white paper roses,

just as alluring and bright

as our poet Blok evoked them.

A bust of Marx, a pioneer scarf,

a packet of blank arrest forms,

the 3rd Congress of the Komsomol,

and a bayonet from the Red Guard.

12

They left the Sailor standing

at the door. They went in.

No sooner had they seen Him

than they became bewildered

and backed away in terror.

Their faces grew pale. They trembled

and dissolved in the air… The Sailor

instantly toppled off the porch

and sprawled out like a worm.

But listen! Already, the horns

13

of battle have begun to sound

from far off in the distance.

Our armor is strong! Our hand

is firm! Our fury is righteous!

The sky quakes with thunder —

propeller, sing your furious song!

And now an NKVD squad

has got the place surrounded…

Translated from the Russian by Jamie Olson

______________

* Anatoly Grigoryevich Zheleznyakov (1895-1919), also known as “Sailor Zheleznyak,” was an anarchist, seaman in the Baltic fleet, and one of the leaders of the Bolshevik revolution in 1917. During the Russian Civil War, he commanded a brigade of armored trains and died from a chest wound sustained in a battle against White army troops in Ukraine.